A few years back I had the job of arranging the speakers for a photography club. There was a regular repeating group of local pundits, so of course I went totally off piste and got people in who did more than the usual landscape and a bit of wildlife. One of these was the (sadly missed) Terry Cryer. Apart from being a wonderful raconteur and a brilliant printer, he was also a great photographer. One of his pictures was a little girl stood in a doorway. He said it was almost too dark to focus, so he threw the film in some D76 diluted 1:100 and left it for a couple of hours. My spider senses were aroused – what was this thing he did? It was stand development, and I was at least a hundred years late to the party. So I parked the idea in memory as something that might come in useful one day.

Day – and I had a roll of film shot under difficult lighting. Very contrasty, with intense highlights and deep shadows. What I needed was a method of holding back the development of the highlights while bringing-up the shadows. There was something rattling in the back of my head about standing around. To t’interweb!

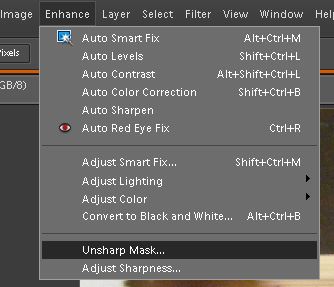

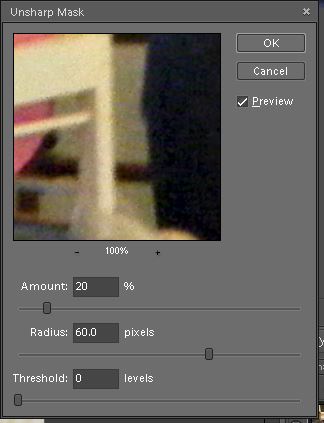

It seemed the answer was semi-stand development in dilute Rodinal. Even more joyous was the message that the same development method and time worked for most films, so I could fill the tank with different types or speeds and get loads of stuff done in one go. So, here we go – Rodinal diluted 1+100; normal agitation for the first minute then leave the tank to stand; one careful inversion every 30 mins; tip it out, wash and fix after two hours. And it worked!

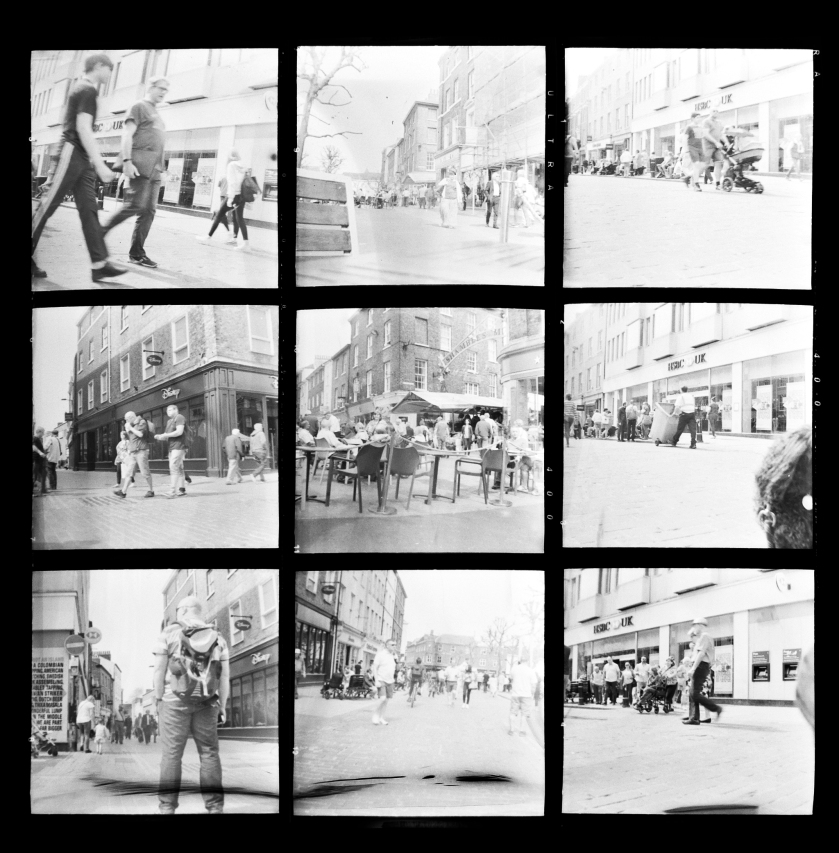

Even better was the news that it could be used on old film or film with unknown sensitivity or exposure. I got a very expired roll of Tri-X as part of the Emulsive Secret Santa with the first couple of frames shot by the donor and me to finish. It worked better than I hoped, even though the film itself was fogged and spotty ( which reminds me of my teenage self).

I had previously tried two-part developer as the magic combination. This too is supposed to preserve the highlights while developing the shadows. The problem is that I seldom got it to work. Unless I made it fresh, my film was grossly under-developed. But the joy of stand development is that the developer is freshly made, just that there is not much of it in the water.

It seems to work though, and it works with pushed film. There are some films that are recommended to not develop with this method, such as Fomapan 320 soft, but my regular diet of HP5 works well. Do I use it all the time? No, I don’t want to take more than two hours to develop a film. I am also worried that I could end up with streaks, so normal film gets normal methods. It’s a useful tool in the box though for when you could have underexposure or a wide exposure range on the film. And isn’t that how you used to tell a Real Engineer – that they had a graded set of hammers?

What about two-part development though? Doesn’t that do the same thing, with less risk of streaking? I would use them to do different jobs. Two-part development works by soaking the film in developer, and then activating just the developer that was absorbed in the film. I would use two-part development when I had greatly overexposed the film. It holds back the highlights because they only have as much developer as they absorbed. So this should be great for pulling film: giving it two or three stops of overexposure so that you get loads of shadow detail. I actually did this as an experiment, photographing a willow tree in full leaf in direct sunlight. Each frame in the sequence was overexposed by an additional stop, but all that happened is the shadow detail increased: the highlights stayed the same. So this is great for when you have to deal with high contrast and want to render it ‘normal’.

I would use semi-stand development for when I had pushed the film. The highlights are held back because they exhaust the developer locally, while the shadows continue to develop. What Terry Cryer did was to push his film with the picture of the little girl: underexpose and then bring it up in development without increasing the contrast too far to be printable. I would also use semi-stand for when I had very mixed scenes on the same film. An example was recently, where I was using an unsophisticated camera to take both night shots and daytime landscapes. Bung the film in the tank and semi-stand it and all the frames turn out OK.

No doubt people use either method to do either job, and I think even my description of them ends up saying that they are the same. For me it’s all just theory anyway: I’ve found two-part developers to be unreliable, while semi-stand uses known good chemicals. So while I might theorise about using different methods, I would use semi-stand for both situations.

And an aside – why semi-stand and not stand? Stand means no agitation at all, and really does risk getting streaky negatives. Semi-stand means agitating a tiny amount; just enough to stop the streaks. And not a double-entendre in sight.

Is it worth trying? For sure, so that you have it there if you ever need it. Give it a go. I’m adamant. (Sorry!)